During my decades of researching chile peppers, one of the most commonly asked questions was why did capsaicin evolve? Most scientists have speculated that the reason was to prevent mammals from eating the pods and destroying the seeds, whereas in birds, the seeds pass through the digestive tract enhanced for germination. (According to scientific thought, this is an hypothesis, or an educated guess based on observation. For hypotheses to become theories, they must be verified and generally accepted as true.) A co-hypothesis held that capsaicin is also a defense mechanism against microbial fungi that invade the pods through punctures made in the outer skin by various insects. But what if these hypotheses were not the real reason for its capsaicin’s evolution? Remember that chile peppers are the only known source of capsaicin.

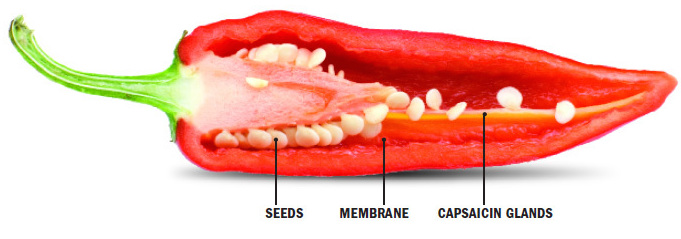

The orange line is the placental tissue where both the seeds and capsaicin reside.

Now consider cannabis, the only known source of tetrahydrocannibinol (THC). Traditional conjecture holds, as is the case with nicotine and caffeine, that the role of THC is to defend the marijuana plant from herbivores and pathogens. But if that’s the case, it doesn’t do a very good job because a number of pests like whitefly, spider mites, thrips, and beetles attack it despite all those trichomes that are producing the THC. And birds eat the seeds and thus spread marijuana, so why would a plant discourage this? Also remember that certain mammals eat the vegetative growth of marijuana, particularly deer and rodents.

Another hypothesis is that THC helps protect against ultraviolet radiation. There is more THC in plants found growing at in high elevations where there are a greater concentration of UV rays. In my viewpoint this is more adaptation than evolution, if, in fact, there is a cause and effect relationship. A final theory holds that it reduces water loss. “Indeed, in very hot climates, the cuticle can split to allow the resin to ooze down the stems,” writes Martin Booth. “When caked on the plant, it hardens to an impermeable, water-insoluble varnish.” Again, I think this is adaptation, not the real reason for the evolution of THC.

Humans have receptors that detect the presence of both capsaicin and THC and send those signals to the brain via the nervous system, blood circulation, or both. Whether it’s a burning sensation or a high, it’s the same process. And where did those receptors come from? I think from the coevolution of mankind with both chile peppers and marijuana.

Put simply, coevolution is the situation where two different species help each other adapt and reproduce by influencing each other. The coevolution of bees with flowers is probably the classic case, and that type of coalition is called mutualistic coevolution because both species receive a benefit as result of it. The flowers get pollinated and the bees receive nectar and pollen. They both enhance the other’s ability to survive and reproduce. It’s my hypothesis that both capsaicin and THC evolved to encourage humans to domesticate these two plants and give the species a much better chance to survive. After all, given the total number of seeds produced by a typical cannabis plant, I think it’s pretty obvious that the higher percentage of seeds will thrive under human care rather than in the wild conditions of the foothills of the Indian Kush. But some people disagree.

A closeup of the trichomes that produce THC in a flowering marijuana top .

In one of his lectures in 2002, Michael Pollan observed: “Why did this plant make THC in the first place, THC being the main psychoactive ingredient? It certainly wasn’t so people could get high. Marijuana did not produce THC so we could change our consciousness.” Robert Connell Clarke, the marijuana botanist, disagrees and writes that “the most obvious evolutionary advantage THC conferred on cannabis was the psychoactive properties which attracted human attention and caused the plant to be spread around the world.”

Pollan reversed his position in The Botany of Desire, noting that the vast majority of botanists have what he calls a “blinkered humanist perspective.” They simply ignore the coevolution of humans and cannabis. “We automatically think of domestication as something we do to other species,” he explains, “but it makes just as much sense to think of it as something certain plants and animals have done to us, a clever evolutionary strategy for advancing their own interests…a dance of human and plant desire that has left neither the plants nor the people taking part in it unchanged.”

What we humans have inherited are endocannabinoids and endocapsaicinoids, compounds within our bodies that are essentially identical to those found in marijuana and chile peppers. One researcher, Dr. Gregory T. Carter of the University of Washington, explained some of the current knowledge of the cannabis-like compounds in our bodies: “It now appears that the cannabinoid system evolved with our species and is intricately involved in normal human physiology, specifically in the control of movement, pain, memory, and appetite, among others. The detection of widespread cannabinoid receptors in the brain and peripheral tissues suggests that the cannabinoid system represents a previously unrecognized ubiquitous network in the nervous system.”

If you agree with Carter’s hypothesis, then you also believe we are pre-programmed to enjoy the high produced by cannabis and the burn resulting from chile peppers. No wonder the “war on drugs” declared by federal authorities can never be won. We are hardwired in our brains to enjoy both drugs: tetrahydrocannabinol and capsaicin.