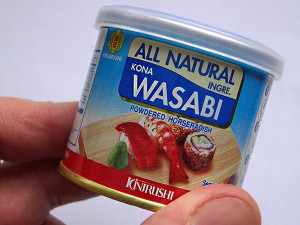

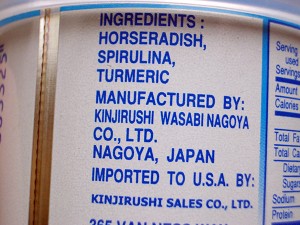

There are many foods and condiments that are not what they seem to be. The “wasabi” served in nearly every sushi bar and Japanese restaurant in North America, and seen in the lower right corner of the board above, is not authentic wasabi. Why not? True wasabi is very difficult to grow because it requires a clear, running stream. Only two or three farms in the United States and Canada grow it, but the demand is enormous. So manufacturers and restaurants create fake wasabi. Wasabi and horseradish have the same chemical in them that creates the “fiery” sensation in your mouth and sinus passages: isothiocyanate. (It’s in mustard and black pepper, too.) So if you mix horseradish, a little mustard, and green food coloring together, you will have an acceptable Japanese condiment: fake wasabi.

My friend Harald Zoschke, who lives in Bardolino, Italy, sent me two photos of packaged wasabi made in Japan:

- Front of Package

- Back of Package

Harald was successful in growing wasabi, when he found a live rhizome in a grocery store:

The original rhizome.

Growing it in a glass of water that must be changed daily. Note the flowers.

Grating the stem for REAL wasabi.

Here’s what I wrote about wasabi for The Spicy Food Lover’s Bible that I wrote with Nancy Gerlach (New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 2005).

When you go to your favorite sushi restaurant and are served the green paste called wasabi, 99 percent of the time you are being served imitation wasabi, made from horseradish, Chinese mustard, cornstarch, and blue and yellow food coloring. Real wasabi is a rare and expensive delicacy that is confined mostly to Japan. In 1999, wholesale prices for wasabi in Japan ranged from $25 to $85 per pound, and retail prices soared to more than $100. Even in Japan, a mere 5 percent of sushi shops can afford to use fresh wasabi. Only recently has real wasabi been made available in the United States; growers like Pacific Farms in Oregon charge about $25 for six 43-gram tubes (about half a pound). They also sell wasabi plants for home gardening, but that is a difficult process.

The Plant and a Familiar Fire Source

There is a dispute over the botanical name of wasabi, a perennial herb native to Japan and eastern Siberia ; some sources give it as Eutrema wasabi, and others Wasabia japonica. Wasabi is said to mean “mountain hollyhock.” Like horseradish, wasabi is cruciferous, related to mustard and cabbage, and it grows about two feet tall. The plant’s most pungent part, as with ginger, is a rhizome. Its pungency comes from allyl isothiocyanate, the same chemical found in horseradish and black mustard. Cultivated varieties of wasabi include ‘Daruma’, the most popular, and ‘Mazuma’, which has more heat. Wasabi has been cultivated in its native Japan since the tenth century, but it is notoriously difficult to grow; its natural environment is in or near cold, shaded mountain streams with just the right mineral balance. Outdoor cultivated wasabi plants require a constant supply of cool, running water, a loose gravel bed, an ambient air temperature between 48° and 64°F, and shade to protect their leaves from the sun. Wasabi can be grown from seed or from rhizome offshoots and requires eighteen months or more to mature. In Japan, growers traditionally constructed wasabi beds up to three feet deep using graduated sizes of gravel placed alongside cold streams, precisely arranged so water runs through them in a uniform pattern. The last such beds in Japan, however, were reportedly built more than two hundred years ago. The highest-quality wasabi is bed-grown and called sawa wasabi; when the plant is grown in fields, it is called oka wasabi, which is generally considered to be inferior in appearance and flavor. It is possible to grow wasabi in pots or in the garden under shade netting, but only if you live in a cool, moist climate, or in an air-conditioned greenhouse, with constant misting. It is grown in semi-aquatic conditions in greenhouses in British Colombia and in straight compost under shade netting in Seattle, where the plants are misted twice daily. On the coast of Oregon, Pacific Farms grows wasabi hydroponically in greenhouses, allowing harvest and replanting every week of the year. In New Zealand wasabi is raised in raised beds in streams. The wasabi harvest usually occurs in the spring, after the plants have established a new set of bright green leaves. The harvested rhizomes with the roots removed resemble knobby, thin, elongated pineapples.

Wasabi and Nutrition

Wasabi has considerable amounts of potassium, calcium, and vitamin C. Since it is consumed in such small quantities, however, it is not a significant source of such nutrients. More significantly, it contains cancer-fighting isothiocyanates; studies in Japan indicate that wasabi is effective against stomach cancer cells. It is thought to be antibacterial, one reason it is eaten with raw fish—to prevent food poisoning. It also has antifungal properties.

Forms

Raw wasabi rhizomes, which can range in size from a couple of inches to nearly a foot in length, are sold in markets in Japan in pans of water. Avoid shriveled rhizomes. Trim off any dark edges before grating and scrub with a brush. Traditionally, a sharkskin grater, or oroshi, is used to transform the rhizome into a fine, pale green paste. If an oroshi is not available, a ceramic grater with very fine teeth is preferred over a stainless steel grater, but the latter can be used. Once the wasabi rhizome is grated, it is rinsed under cool water, drained, formed into a ball, and allowed to stand at room temperature for at least five minutes for the flavors to fully form. It should be consumed within twenty minutes, before its pungency dissipates. As is most wasabi paste, “wasabi powder” from Japan is an imitation. In Asian markets, wasabi is sometimes available in pickled form: the leaves, flowers, stalks, and rhizomes are chopped, brined, and mixed with sake, mirin, and sugar. In Japan, a wasabi wine and a wasabi liqueur are available.

Storage

Keep the wasabi rhizomes wrapped in damp paper towels in the refrigerator, where they will last about a month. Rinse in cold water once a week. Culinary Uses

Freshly grated wasabi, mixed with soy sauce, is familiar as a condiment with sushi and sashimi. It is also added to soups and noodle dishes in Japan. American growers have used wasabi in drinks, in appetizers like pâté, in dips and sauces, in salad dressings, and in seafood and meat entrées.